Stage

Justify your answer!

Type de poste : IA, Sciences et Technologies des langues

Publié le

Supervisors

- Thomas Gerald, Université Paris Saclay, LISN

- Sahar Ghannay, Université Paris Saclay, LISN

Keywords

Natural Language Processing, Question Answering, Visual Question Answering, Corpus annotation, Deep-

Learning

Project Description

A fundamental question in generative textual approaches is to retrieve what part of the internal knowledge or

contextual knowledge is used for the generation.

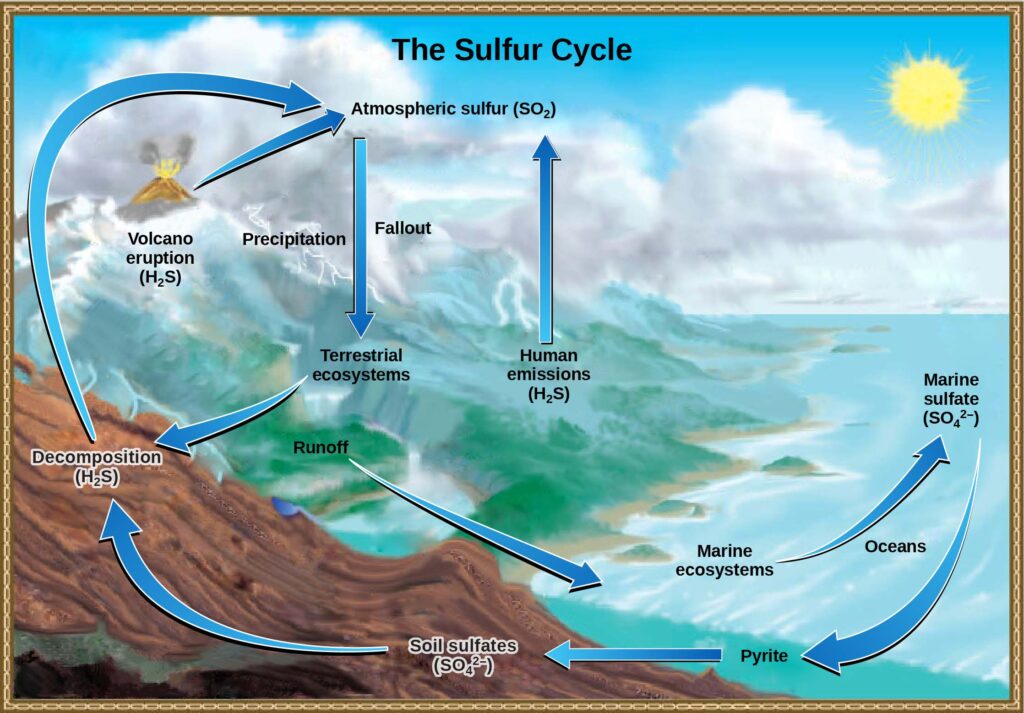

To illustrate our research question, let us consider the figure below1 and the question ”What are the sources

of Atmospheric sulfur ?”. A short answer could be ”Atmospheric sulfur came from soil decomposition, human

emissions and less frequently from volcanic eruption; to provide this answer, the model should gather specific

information from the figure and the text. Nonetheless, some prior knowledge is necessary, such as linking the

arrow to a flow or process text included in the image.

This example illustrates our two objectives: identifying which part of the context the model leverages to

answer the question, and determining which part of preliminary knowledge (from a pre-trained model) is utilised

to answer the question.

Deep learning generative architectures that leverage both text and image have led to substantial improvements

in the complex question-answering task [Radford et al., 2021]. While working efficiently on photographs,

a few approaches are practical when working with complex images or schematics (such as diagrams or maps) in conjunction with textual information. Most importantly, disentangling part of the knowledge serving generation

remains difficult, e.g. does the model use pre-trained knowledge or a specific part of the context? In the literature,

previous studies have begun to explore the topic of explainability. Beyond them, different approaches arose:

observing internal signal in LLMs activation (e.g. attention weights) [Bibal et al., 2022], enforcing generation

of explanation/justification alongside the answer [Wei et al., 2022, DeepSeek-AIArtificial Intelligence et al., 2025] or disentangling

memory from reasoning [Jin et al., 2025]. While these methods may support the content, they are primarily

developed to improve performance, rather than to provide an explanation. The goal of the internship is thus

twofold: to evaluate grounding explanation methods and estimate how these approaches depict the internal

behaviour of the model; and to propose a new framework pipeline that allows for discovering what supporting

context is used for generation and what part leverages internal model capacities or knowledge.

Today, we have gathered a dataset that considers, simultaneously, schematics and text passages collected

from the schoolbook corpus (on biology and history). The first experiments conducted on generating questions

and answers from multimodal documents, alongside an evaluation of specific domain criteria, will serve as a

starting point for the subject.

To discover the context implication in models (versus internal knowledge), the intern could start with a

simple pipeline to measure the impact of the different contexts on the generation, for instance :

- Modify/noising specific part of the context (blurring images, replacing named entities, …)

- Measure the difference in the generated answer with/without noisy context

- Identify signals in activation (or attention mechanisms) correlating to the type of noise

Depending on the advances, experiments to control internal/contextual knowledge in generation would be led.

Internship objectives

The objective of the internship is to develop/propose new explanability methods considering the generation of

question-answer pairs in VLLM approaches. The first month of the internship will be dedicated to producing a

bibliography on explainability in LLMs and VLLMs architectures. To build explainability modules or methods, a

deep understanding of VLLM-like architectures is required. In a second step, the intern will work on a collection

of mid-sized documents (≈ 4000 tokens) and testDéfinition courte Lorem ipsum the different explainability approaches on an education QA

corpus. In the final step, the student will propose a new pipeline for explainability, focusing on the contextual

content involved in generation, and, with the aid of their supervisor, develop a method to evaluate the quality of

the designed methods efficiently. If necessary, a human evaluation campaign could be envisioned to strengthen

the study. A good internship would lead to the realisation of a PhD.

Practicalities

The internship will be funded at 659.76 € per month for a duration of 6 months (starting in February or March

2025) and will take place at the LISN laboratory (CNRS, Paris Saclay).

Candidate Profile

We are looking for highly motivated candidates with a strong interest in academic research and the will to

pursue a PhD. We also require the following qualifications:

- Education: Master’s degree (M2) in Computer Science, with a preference for candidates experienced in

Natural Language Processing (NLP), Computer Vision (CV), or Artificial Intelligence (AIArtificial Intelligence). - Technical Skills:

– Proficiency in Python and familiarity with deep learning libraries such as TensorFlow, PyTorch, or

Keras.

– Experience in data analysis and information extraction tools. - Soft Skills: Strong analytical abilities, an interest in accessibility and human-centric AIArtificial Intelligence, and the ability to

work independently and collaboratively in a research environment.

References

[Bibal et al., 2022] Bibal, A., Cardon, R., Alfter, D., Wilkens, R., Wang, X., Fran¸cois, T., andWatrin, P. (2022).

Is attention explanation? an introduction to the debate. In Muresan, S., Nakov, P., and Villavicencio, A.,

editors, Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume

1: Long Papers), pages 3889–3900, Dublin, Ireland. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[DeepSeek-AIArtificial Intelligence et al., 2025] DeepSeek-AIArtificial Intelligence, Guo, D., Yang, D., Zhang, H., Song, J., Zhang, R., Xu, R., Zhu, Q.,

Ma, S., Wang, P., Bi, X., Zhang, X., Yu, X., Wu, Y., Wu, Z. F., Gou, Z., Shao, Z., Li, Z., Gao, Z., Liu, A.,

Xue, B., Wang, B., Wu, B., Feng, B., Lu, C., Zhao, C., Deng, C., Zhang, C., Ruan, C., Dai, D., Chen, D.,

Ji, D., Li, E., Lin, F., Dai, F., Luo, F., Hao, G., Chen, G., Li, G., Zhang, H., Bao, H., Xu, H., Wang, H.,

Ding, H., Xin, H., Gao, H., Qu, H., Li, H., Guo, J., Li, J., Wang, J., Chen, J., Yuan, J., Qiu, J., Li, J., Cai,

J. L., Ni, J., Liang, J., Chen, J., Dong, K., Hu, K., Gao, K., Guan, K., Huang, K., Yu, K., Wang, L., Zhang,

L., Zhao, L., Wang, L., Zhang, L., Xu, L., Xia, L., Zhang, M., Zhang, M., Tang, M., Li, M., Wang, M., Li,

M., Tian, N., Huang, P., Zhang, P., Wang, Q., Chen, Q., Du, Q., Ge, R., Zhang, R., Pan, R., Wang, R.,

Chen, R. J., Jin, R. L., Chen, R., Lu, S., Zhou, S., Chen, S., Ye, S., Wang, S., Yu, S., Zhou, S., Pan, S., Li,

S. S., Zhou, S., Wu, S., Ye, S., Yun, T., Pei, T., Sun, T., Wang, T., Zeng, W., Zhao, W., Liu, W., Liang,

W., Gao, W., Yu, W., Zhang, W., Xiao, W. L., An, W., Liu, X., Wang, X., Chen, X., Nie, X., Cheng, X.,

Liu, X., Xie, X., Liu, X., Yang, X., Li, X., Su, X., Lin, X., Li, X. Q., Jin, X., Shen, X., Chen, X., Sun, X.,

Wang, X., Song, X., Zhou, X., Wang, X., Shan, X., Li, Y. K., Wang, Y. Q., Wei, Y. X., Zhang, Y., Xu, Y.,

Li, Y., Zhao, Y., Sun, Y., Wang, Y., Yu, Y., Zhang, Y., Shi, Y., Xiong, Y., He, Y., Piao, Y., Wang, Y., Tan,

Y., Ma, Y., Liu, Y., Guo, Y., Ou, Y., Wang, Y., Gong, Y., Zou, Y., He, Y., Xiong, Y., Luo, Y., You, Y., Liu,

Y., Zhou, Y., Zhu, Y. X., Xu, Y., Huang, Y., Li, Y., Zheng, Y., Zhu, Y., Ma, Y., Tang, Y., Zha, Y., Yan,

Y., Ren, Z. Z., Ren, Z., Sha, Z., Fu, Z., Xu, Z., Xie, Z., Zhang, Z., Hao, Z., Ma, Z., Yan, Z., Wu, Z., Gu,

Z., Zhu, Z., Liu, Z., Li, Z., Xie, Z., Song, Z., Pan, Z., Huang, Z., Xu, Z., Zhang, Z., and Zhang, Z. (2025).

Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning.

[Jin et al., 2025] Jin, M., Luo, W., Cheng, S., Wang, X., Hua, W., Tang, R., Wang, W. Y., and Zhang, Y.

(2025). Disentangling memory and reasoning ability in large language models.

[Radford et al., 2021] Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Hallacy, C., Ramesh, A., Goh, G., Agarwal, S., Sastry, G.,

Askell, A., Mishkin, P., Clark, J., Krueger, G., and Sutskever, I. (2021). Learning transferable visual models

from natural language supervision. In ICML, volume 139 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pages

8748–8763. PMLR.

[Wei et al., 2022] Wei, J., Wang, X., Schuurmans, D., Bosma, M., Xia, F., Chi, E., Le, Q. V., Zhou, D.,

et al. (2022). Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural

information processing systems, 35:24824–24837.